The founder’s birth

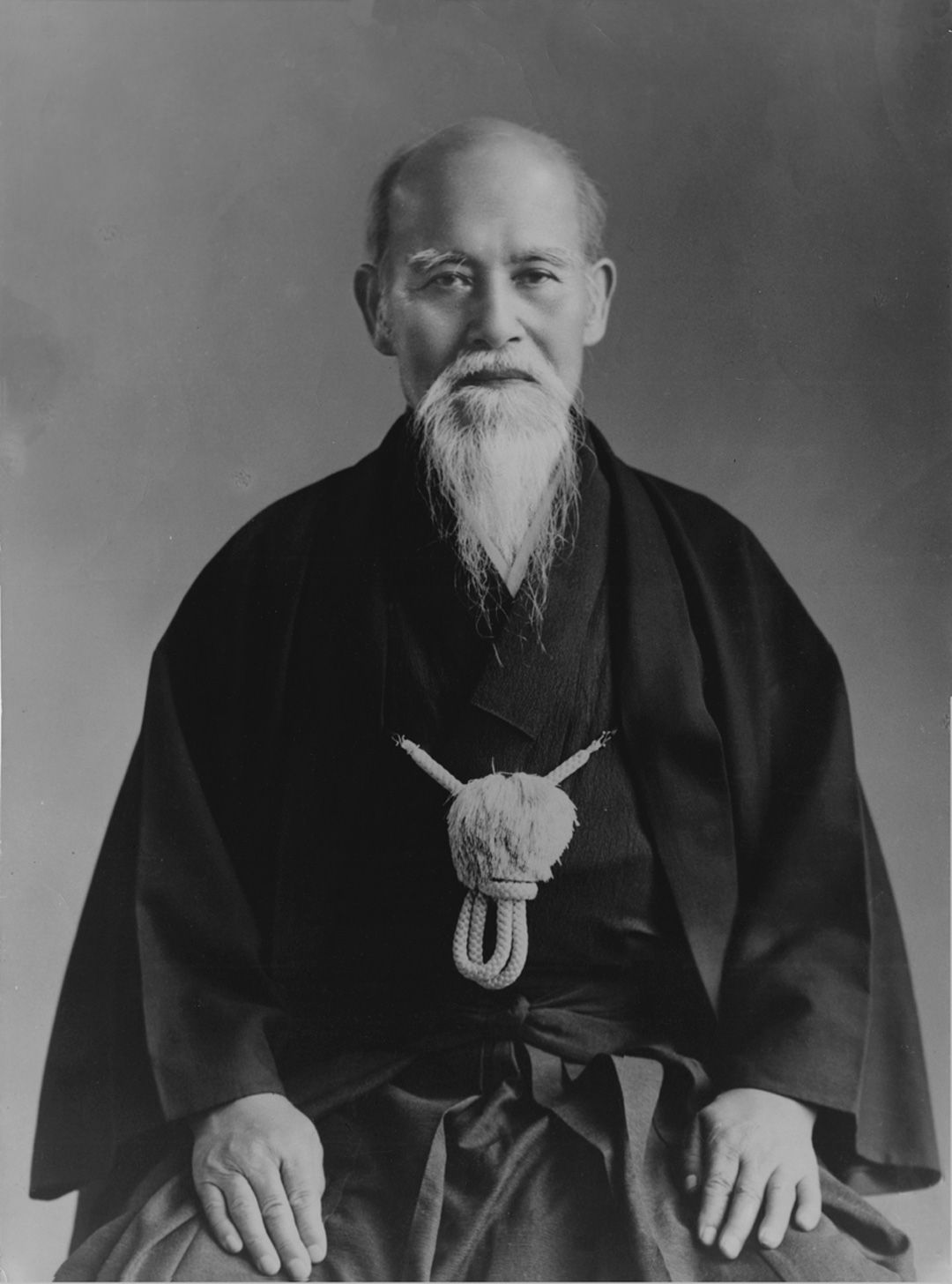

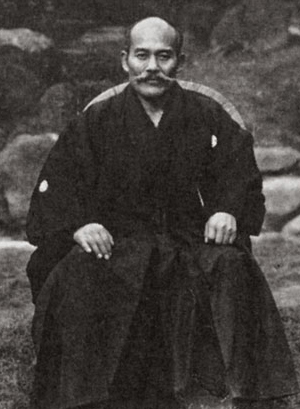

Master Ueshiba was born on December 14, 1883, in the city of Tanabe, located in Wakayama Prefecture in southern Japan. He was the fourth child in the Ueshiba family and the only son.

Young Ueshiba grew up in a privileged environment. His mother, Yuki Itokawa, was a descendant of a noble family from the Takeda clan, and his father, Yoroku Ueshiba, was a wealthy farmer who was also involved in local politics as a municipal councilor.

Morihei was reportedly a premature baby, frail in constitution, and often sick. To help him improve his health and encourage him to strengthen his body, his father became deeply involved in his development and taught him the secret martial art of Aiki-ryu, a blend of Tai-Jitsu and Kendo. He also enrolled him in swimming and sumo schools. Morihei Ueshiba was seven years old at the time. His father would often tell him stories about his great-grandfather Kichiemon, whom he described as a great samurai. Inspired by these stories and by witnessing his father being attacked by bandits, Morihei became determined to grow strong. To that end, he worked with fishermen and took part in numerous wrestling contests.

Morihei’s parents also introduced him to the fine arts, such as painting, calligraphy, and literature. He was introduced to religion at the age of six when he was sent to study at the Jizoderu temple, where he studied major Confucian texts. Through his teachers, he was also introduced to Shintoism and Shingon Buddhism, for which he showed great interest. His education continued, and he graduated from the Yoshida Abacus Institute, a private school where he studied accounting.

After working for a few months at the Tanabe tax office and encouraged by his parents and other family members, Morihei Ueshiba moved to Tokyo, where he founded the “Ueshiba Trading Company,” specializing in the distribution of school supplies. During this time, he also studied Jujutsu at the Tengin Shinyo-Ryu school under Tokusaburo Tojawa Sensei, as well as Kenjutsu from the Shinkage Kenjutsu school.

Military Service

A few months later, weakened by beriberi, Master Ueshiba had to leave Tokyo and returned to his hometown of Tanabe to recover.

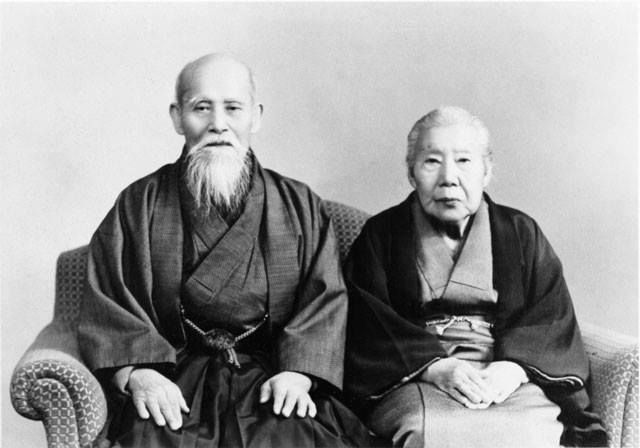

That same year, he married Hatsu Itokawa, a distant relative he had known since childhood.

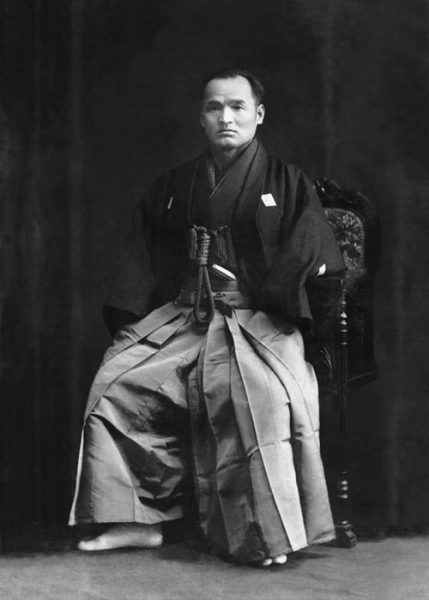

Drawing lessons from his brief stay in Tokyo, the young Ueshiba realized he was not suited for business. Seeking adventure, he decided in 1903 to enlist in the Japanese army, which was then in conflict with Russia.

At first, he was rejected for being too short. To try to overcome this, Ueshiba tied heavy weights to his legs and hung from tree branches for hours in an attempt to stretch his spine. He was eventually accepted and enlisted in the 37th Regiment of the Fourth Division in Osaka.

During bayonet training, Ueshiba’s exceptional martial arts skills quickly became apparent. He was nicknamed the “God of Soldiers” due to his remarkable proficiency with the bayonet and Juken-jutsu, as well as his work ethic and deep honesty. Ueshiba continued to train during his military service, notably under Masakatsu Nakai of the Goto school of Yagyu-Ryu Jujutsu.

Less than a year after joining the army, Morihei Ueshiba was promoted to corporal, and in 1904, he was sent to the front during the Russo-Japanese War, from which he returned with the rank of sergeant.

Around 1906 or 1907, Ueshiba was demobilized and returned to civilian life. He continued to train with Masakatsu Nakai and received a diploma from the Goto school in 1910. He eventually returned to Tanabe, and in 1911, his first daughter, Matsuko Ueshiba, was born. That same year, Morihei began studying Judo under Kiyoichi Takagi.

The Journey to Hokkaido

Morihei Ueshiba became interested in a government colonization plan for the northern island of Hokkaido.

In March 1912, with financial support from his father Yoroku Ueshiba, he led a group of about fifty families—more than eighty people in total—and guided them to settle in a remote part of the island’s north. These settlers founded the village of Shirataki.

Life for the settlers was difficult due to poor soil and harsh weather. Ueshiba’s group, known as the Kishu group, mainly engaged in agricultural and forestry work. Morihei also took part in local political life as a territorial councilor and initiated several projects, including the construction of a commercial street and a school.

In early 1915, an event profoundly marked Master Ueshiba’s life. In the town of Engaru, he met Sokaku Takeda Sensei, a master of Daito-Ryu Jujutsu living on the island of Hokkaido. This encounter would prove pivotal in the future development of Aikido.

Barely thirty-two years old at the time, Morihei Ueshiba was already highly skilled in martial arts, but he was far from matching Takeda Sensei. The number of techniques Takeda practiced—both complex and powerful—fascinated Morihei. From then on, he devoted much time and money to learning them. He even invited Sokaku to live in his home so that he could benefit from private lessons. These private lessons were expensive, and his father Yoroku Ueshiba supported him financially by sending funds from Tanabe.

Quickly becoming one of Takeda’s top students, Morihei Ueshiba received a first-level instructor’s diploma in Daito-Ryu in 1917. The techniques he learned during this time would form the foundation of what would later become Master Ueshiba’s Aikido. It was also during this period that his first son, Takemori Ueshiba, was born.

The Encounter with Onisaburo Deguchi

In 1919, Morihei Ueshiba received a telegram informing him of the serious illness of his father, Yoroku. He ended his stay in Shirataki as well as his training in Daito-Ryu and set out for Tanabe to be at his dying father’s bedside. Morihei gave all his possessions—his modest home and furniture—to his teacher Sokaku Takeda.

During the journey to Tanabe, Master Ueshiba heard about the extraordinary healing powers of a religious leader named Onisaburo Deguchi. Morihei then traveled to the small town of Ayabe, near Kyoto, to meet this spiritual leader and ask him to pray for his father’s recovery.

The meeting with Onisaburo— a charismatic figure in the Omoto-Kyo religion and renowned for his Chikon Kishin (a meditation technique aimed at achieving serenity and communion with the divine)—profoundly changed Ueshiba’s life. While Sokaku Takeda had influenced him through martial techniques, Onisaburo Deguchi would shape his worldview through spiritual ideology and teachings about life. Morihei Ueshiba ultimately decided to stay in Ayabe for a few days before continuing to Tanabe.

By the time Morihei arrived in Tanabe, his father Yoroku Ueshiba, aged 76, had already passed away on January 2, 1920. Grieved by his father’s death and criticized by his family for not arriving in time, Morihei spent several days in the mountains, training in Kenjutsu, before returning to Ayabe, where he settled with his family a few months later.

It was in Ayabe, in 1920, that Ueshiba’s second son, Kuniharu, was born. Sadly, both Kuniharu and his first son Takemori—then three years old—passed away in the same year.

In 1921, Master Ueshiba’s third son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba, was born. He would go on to become the future Doshu (head) of Aikido. That same year, Onisaburo Deguchi invited Morihei to become a martial arts instructor and had a dojo built for that purpose. Master Ueshiba thus began teaching Daito-Ryu Jujutsu to members of the Omoto religion, while continuing his training with Takeda Sensei, who visited him frequently. In 1922, Takeda awarded Morihei the title of Kyori Dairi (assistant instructor).

Morihei Ueshiba’s reputation and renown began to grow, thanks to his association with Onisaburo Deguchi and the high quality of his instruction at his dojo.

It was also in 1922 that Morihei Ueshiba’s mother passed away.

The Mongolian Expedition

Onisaburo Deguchi had grand ambitions to expand the influence of the Omoto religion. He shared with Morihei Ueshiba and a small group of followers his plan to establish a religious state in Mongolia, where at the time Chinese and Japanese armies were clashing. This envisioned kingdom would serve as a spiritual center for universal love and brotherhood, based on the principles of Omoto-Kyo.

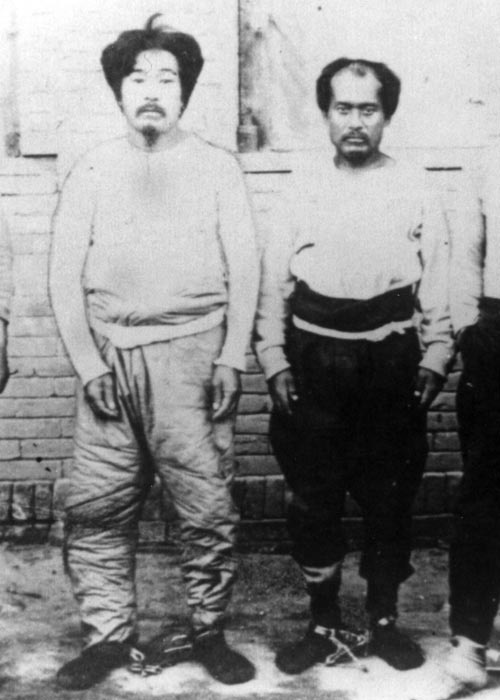

In 1924, at the invitation of Yutaro Yano (a retired naval commander), Onisaburo Deguchi, Ueshiba, and a group of close companions traveled to Mongolia to carry out this plan. There, they allied with a Chinese rebel named Lu Chang K’uei to accomplish their mission.

It was during this expedition that the famous episode occurred in which Master Ueshiba, threatened by enemies armed with rifles, claimed to see the trajectory of the bullets as lines of light, allowing him to dodge them with ease.

Unfortunately, Ueshiba and his group were captured by Chinese troops and sentenced to death. Their ally Lu Chang K’uei and his men were executed, but the Japanese members of the group narrowly escaped execution thanks to a last-minute intervention by the Japanese consulate. Several photographs taken during their captivity bear witness to the hardship they endured.

The surviving members were escorted back to Japan under strict supervision, and Onisaburo Deguchi was imprisoned. Master Ueshiba decided to return to Ayabe.

The Return to Japan

Morihei Ueshiba returned to Ayabe to resume teaching martial arts at the Ueshiba Academy and worked on the Tennodaira farm. At that time, he took a particular interest in teaching Sojutsu (the art of the spear), Kenjutsu, and Jujutsu. Among his Daito-ryu students were several naval officers, including the distinguished Admiral Seiko Asano, who was also a follower of the Omoto religion.

Gradually, news of Master Ueshiba’s skills spread. Seiko Asano praised Morihei Ueshiba to his naval colleagues and encouraged another admiral, Isamu Takeshita, to discover the martial art taught by Morihei. Admiral Takeshita was very impressed and used his influence to enable Morihei to give demonstrations and lead training seminars in Tokyo.

In 1925, an event occurred that radically changed Master Ueshiba’s view of the martial arts. He accepted a challenge from a naval officer who was a master of Kendo and won the fight without really fighting. He did not use his sword but instead avoided or deflected the officer’s strikes because he was able to visualize the trajectory of the attacks before they were made. After the fight, Master Ueshiba, exhausted, retreated to his garden to refresh himself by the well. A feeling of great peace and serenity washed over him. It seemed to him that he was bathed in a golden light descending from the sky. His body and mind became gold. This intense and unique experience was his personal revelation, his Satori (spiritual awakening).

Master Ueshiba said:“Suddenly, I felt the universe tremble, and a golden energy rose from the earth, surrounding my body with a veil, transforming it into a body of gold. At that very moment, my body and spirit became luminous. I could understand the song of the birds and became aware of God’s thought… In an instant, I understood the nature of creation, the warrior’s path, which is to spread divine love.”

Aikido was born! O Sensei Ueshiba named this teaching aiki-budo rather than aiki-bujutsu.

The substitution of the character dō for jutsu changes the spirit of the study entirely: it shifts from the “martial technique of aiki” to the “martial way of aiki.”

In 1927, Ueshiba and his family settled in Tokyo. This move to the capital allowed Master Ueshiba to teach his art to highly influential people, including politicians, military officers, and members of the imperial guard.

Establishing in Tokyo

At the beginning of his move to Tokyo, Master Ueshiba taught in the private residences of several of his patrons, including that of Admiral Takeshita. Takeshita was a very passionate student; he had served as president of the Sumo Association and was a strong supporter of Master Ueshiba. He worked tirelessly to promote Master Ueshiba and his art in various circles. This support was certainly crucial to the success Master Ueshiba enjoyed in Tokyo.

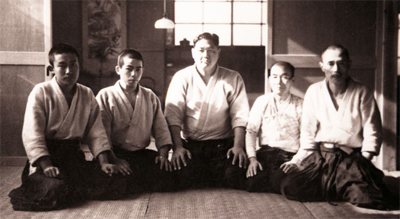

In 1930, a fundraising effort made it possible to open a dojo in Ushigome, a district of Shinjuku, which Ueshiba named Kobukan. This remains the headquarters of the Aikikai to this day. There, he received a visit from Jigoro Kano Sensei, the master of Kodokan and founder of Judo. Master Ueshiba’s techniques deeply impressed Kano, who entrusted several of his best students to Ueshiba to learn Aikido. The Kobukan was then nicknamed the “Dojo of Hell.”

Among Master Ueshiba’s students were renowned Aikido practitioners such as Yoichiro Inoue, Kenji Tomiki, Minoru Mochizuki, Tsutomu Yokawa, Shigemi Yonekawa, Rinjiro Shirata, and Gozo Shioda.

In 1931, at the initiative of Onisaburo Deguchi, the Association for the Promotion of Martial Arts was created with the goal of promoting Morihei Ueshiba’s work in the martial arts. Branches of this school were established throughout Japan and organized martial arts training seminars alongside local Omoto religion meetings. This organization was active from 1931 to 1935, when the Omoto-Kyo religion was banned by the Japanese military government.

In 1935, Master Ueshiba also traveled to Osaka to give classes. It was on this occasion that a demonstration was featured in the Asahi newspaper.

Also in 1935, in Osaka, Master Ueshiba and Master Takeda met for the last time, as their relationship had deteriorated over time.

Between 1939 and 1940, Morihei Ueshiba was contracted to teach martial arts at various military academies such as the naval school, the Toyama Officer School, the Nakano spy school, and others. However, in reality, Ueshiba often delegated teaching to advanced Kobukan students due to his very busy schedule.

In 1939, Master Ueshiba was invited to Manchuria to give a public demonstration. He faced the former sumo wrestler Tenryu and pinned him to the ground; Tenryu then became his student. Master Ueshiba returned to Manchuria several times, the last time being in 1942 for the tenth anniversary of the creation of the state of Manchuria. On that day, O Sensei performed his demonstration before Emperor Pu’Yi.

On April 30, 1940, the Kobukan received official recognition as a “Training Institution approved by the Ministry of Health and Hygiene.” Admiral Isamu Takeshita became the first president of the Kobukan.

Aikikai Tokyo

The demonstration before Emperor Pu’Yi had a great impact among foreign dignitaries. Although Master Ueshiba was never a supporter of such exhibitions, he understood that Japan was entering a new era, and so he allowed it to happen. On August 7, 1952, the Aiki temple in Iwama hosted a grand festival celebrating Master Ueshiba’s sixty years of practice. In 1964, O Sensei Ueshiba received a special distinction from Emperor Hirohito in recognition of his exceptional contribution to the martial arts.

On March 14, 1967, the construction of a new Hombu Dojo, a three-story building, was launched. It was completed on December 18 of the same year. Morihei Ueshiba reserved only one room for working and sleeping. The current Hombu Dojo has five floors, housing three dojos and welcoming more than 500 members. Over 30 instructors take turns teaching daily classes, seven days a week.

The Aikikai Foundation, founded in 1940 by Kishomaru Ueshiba, today holds a privileged position within the global Aikido community. More than half of the national Aikido organizations remain affiliated with the Tokyo Aikikai, which serves as the International Aikido Federation.

Other styles of Aikido are now practiced:

-

Yoshinkan Aikido, created by Gozo Shioda, emphasizes a powerful pre-war style.

-

Shinshin Toitsu Aikido, created by Koichi Tohei, is a health method incorporating Aikido techniques focused on the concept of KI.

-

Tomiki Aikido, developed by Kenji Tomiki, includes a competitive aspect.

-

Yoseikan Aikido, created by Minoru Mochizuki, is a blend of Aikido, Judo, Karate, and Kenjutsu techniques.

Iwama, the Sanctuary of Aikido

Towards the late 1930s, the Japanese army became deeply involved in the war effort. Most of Master Ueshiba’s young students were conscripted into the military. This thinning of the Kobukan dojo ranks led to a reduction in its activities just as the Pacific War began.

In 1942, after falling ill from a serious intestinal disease, Master Ueshiba decided to establish a new base for the Aikido organization in Ibaraki Prefecture, in the village of Iwama, where he had purchased land a few years earlier. He entrusted the management of the dojos in Wakamatsu-cho to his son Kisshomaru Ueshiba.

At Iwama, O Sensei began the construction of what he called the Ubuya (“place of birth”), the sacred circle of Aikido: a complex including the Aiki altar and an outdoor dojo. This was completed in 1964 by a beautiful set of forty-three guardian deity sculptures of Aikido. The dojo, now known as the Ibaraki Dojo, was finished in 1945 just before the end of the war. There, away from the turmoil in Tokyo caused by the war, O Sensei dedicated himself to agriculture, training, and meditation.

These years spent in Iwama proved decisive for the development of modern Aikido. Morihei Ueshiba focused all his energy on intensive training to perfect his martial art dedicated to the peaceful resolution of conflict.

By the end of the war, O Sensei had few students in Iwama, as many pre-war disciples had scattered across Southeast Asia.

It was during this period, in the summer of 1946, that a young man employed by the Japanese National Railways joined the Iwama dojo. Morihiro Saito would become one of O Sensei’s closest students and later his technical successor.

Master Ueshiba deepened the study of the sword, known in Aikido as Aiki Ken, and the staff, called Aiki Jo. He believed it was fundamental to understand the handling of these weapons to correctly execute empty-hand techniques.

He then developed a comprehensive Aikido program including weapons practice alongside unarmed techniques. During this time, young Saito often served as O Sensei’s training partner, allowing him to discover many techniques that O Sensei rarely taught.

While living in Iwama, Master Ueshiba defined the concept of Takemusu Aiki, which corresponds to the spontaneous execution of an infinite number of techniques adapted to any kind of attack.

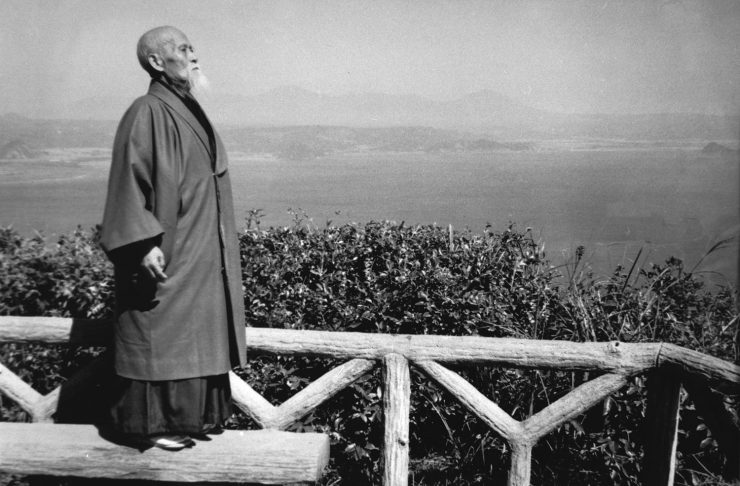

During the 1950s, Master Ueshiba traveled extensively throughout Japan to respond to countless requests. He also spent a few days each month in Tokyo before returning to Iwama. At this time, it was very difficult to predict from day to day where Master Ueshiba would be or when he would stop to teach at the Aikikai in Tokyo. Many students who began training after the war and had the chance to see the founder teach or demonstrate Aikido were enthusiastic about the energy and beauty of his movements, as well as his martial arts ethics.

At this stage, his technique flowed like a river from his spirit, limitless and fundamentally different from the extremely rigorous practice highlighting physical strength that characterized his younger years. During his last years, as his health declined, Master Ueshiba moved less quickly and freely, adapting his techniques by shortening them. O Sensei would project his students with a quick gesture or a slight hand movement, sometimes without even touching them. This phase coincided with the early international spread of Aikido through public demonstrations and film distribution, inspiring many imitators who did not understand that this Aikido was a natural continuation of his past experiences and the result of over sixty years of practice—not a new beginning.

Morihei Ueshiba passed away from liver cancer on April 26, 1969. On the same day, O Sensei received a final posthumous distinction from Emperor Hirohito. His ashes rest in the Ueshiba family temple in Tanabe, and locks of his hair were preserved as relics on the Aiki altar in Iwama, in the family cemetery of Ayabe, and at the grand Kumano altar. His son Kisshomaru Ueshiba succeeded him as the second Doshu of Aikido.